Popular

Clair-Obscur Effects: Times for 2024

Lunar X & V, the Face in Albategnius, the Eyes of Clavius, the Jewelled

Handle and Cassini’s Moon Maiden

by Mary McIntyre

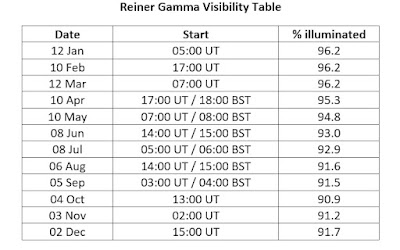

NOTE: I've had to show the tables showing the times of these as jpeg screenshots because this blog interface keeps scrambling my tables. I've saved this entire blog in PDF form so if you are using electronic reading software, you can view the document here.

My You Tube video to accompany this blog is here.

For the past few years I have produced a table showing the

times that the Lunar X and V are visible for the coming year. I know these are the most popular of the

Clair-Obscur effects but they are not the only ones, so last year I added the

Face in Albategnius and the Eyes of Clavius. This year I’ve included an

additional two; the Jewelled Handle AKA Sinus Iridum and Cassini’s Moon Maiden Promontorium

Heraclides, plus a bonus fun one at the end! Hopefully this will give you something new to tick off your lunar observing

list. Detailed information about these effects is below, but for those of you

who are only interested in the data tables, I’ve put those first. The moonrise/moonset times are for Oxford, UK,

and will vary slightly across the UK. The times are listed in UT so if you’re

outside of the UK you can convert this to your own local time then and check

the moonrise and set times for your area.

The Lunar X and V

The Lunar X and V photographed by Mary McIntyre

Lunar X and V Visibility Table

The Face in Albategnius

The Face in Albategnius photo by Mary McIntyreApproximately 2 hours after the Lunar X is at

its best,

when the terminator has moved across to cover the area around it, take a close

look at the shadows on the right hand side of the crater Albategnius (located

almost halfway between the X and V). At just the right time the shadow looks

like the side profile of a face. This shows up more clearly on stacked photos

which have better resolution and sharper features. The above image was taken

with a William Optics 70mm refractor with Celestron 3x Barlow. The camera was

an ASI120MC. This is another short-lived Clair-Obscur effect, so make sure you

don’t miss it!

The Eyes of Clavius

The Eyes of Clavius photo by Mary McIntyre

The Eyes of Clavius Visibility Table

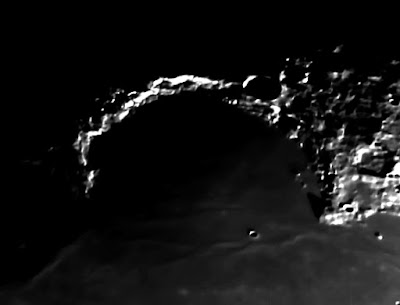

The Jewelled Handle

The Jewelled Handle AKA Sinus Iridum photo by Mary McIntyreThis

clair-obscur effect is best viewed at the start time below but remains visible

after the lunar terminator has passed over the region so it should therefore be

visible for a large part the dates listed below.

The Jewelled Handle Visibility Table

Cassini's Moon Maiden

Cassini’s Moon Maiden AKA Promontorium Heraclides photo by Mary McIntyre

Cassini’s

Moon Maiden starts to become visible and is at its best as the Sun rises over

Sinus Iridum and illuminates Promontorium Heraclides, then remains visible for

a couple of days. The times below are just a guide.

BONUS: Barry Manilow on the Moon?!

Barry on the Moon AKA Montes Caucasus photo by Mel Gigg

A couple of years ago I saw a photograph taken by Mel Gigg

which showed amazing shadows along the Montes Caucasus mountain range in the

north eastern quadrant of the Moon. The shadows from the southern cluster of

peaks show another side profile of a face and there is a peak that was just

catching the light to produce an eye. The highlands around the shadow look like

hair and as soon as I saw it, I immediately thought of Barry Manilow! This is a

fun additional effect to look for, and although the facial profile is visible

for quite a while, the eye is only visible for about 3-4 hours.

Barry Manilow on the Moon Visibility Table

Additional information

if you’re new to these effects

The times given in the data tables are in 24 hour clock and

are in UT/GMT (and BST where appropriate) so you will need to correct for time

zones and daylight time savings if you are not in the UK. I have also included

the approximate moonrise and moonset times in the tables for the effects that

are time critical. These times were taken from the Time and Date website and

relate to my location in Oxford, UK. Your exact rise and set times will vary

depending on where you are in the UK. You can check sunrise and set times for

your location here:

To ascertain the times these effect appear each month, I

used the NASA Scientific Visualisation Studio Moon Phase and Libration tool for

2024: https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/5187/

The Lunar X and V

Lunar X and V photos by Mary McIntyre

The Lunar X and V are transient Clair Obscur effects which

are visible on the lunar surface once a month for about four hours. The “X” is

caused by light illuminating the rims of craters Blanchinus, La Caille and

Purback. The “V” is caused by light illuminating crater Ukert along with

several smaller craters. The X is at its

most striking when it is visible on the shadow side of the terminator. The X is

located about a quarter of the way up from the bottom, and the V is

approximately half way up just inside the illuminated side of the terminator,

and it really shines brightly against the darker background of Mare Vaporum. Once

you know where to look, you will be able to spot them with large binoculars (it

will help if they are mounted) but they are best viewed through a telescope.

They will show up on photos taken with a 300mm zoom lens or through a modest

telescope.

They will remain visible against the lunar surface for a few

hours even after the terminator has moved over them as shown in the inset box on the photo

above.

The X and V are visible close to the First Quarter phase,

however, due to libration, the exact time that they are visible is different

from month to month. The lunar phase illumination at the time they’re seen during

2024 varies between 41.9% and 54.3%. They occur every month but time that they’re

visible may not coincide with the Moon being above the horizon from your

location, so you will not see them every month.

From the UK, the Lunar X is visible seven times

during 2024, but only two of them are when it’s fully dark. Clair-Obscur effects

are more difficult to observe in daylight or when the Moon is rising or setting

so January and March are by far our best opportunities.

In previous years when I’ve observed the Lunar X using the

start times from this tool, I have found it may take about 45 minutes from the

start time before the X becomes clearly visible. The V tends to become visible

a little earlier than the X. The start times are approximate, and they should

be visible for a few hours after this. There

is no fixed end-time listed because as mentioned above, these features remain

visible even after the terminator moves across them, but if you assume they are

visible for around four hours from the start time, you will see them at their

best.

It’s really great fun to observe how the Lunar X and V

regions evolve over time, so if you do make the effort to see them when they

first appear, make sure you check that region again periodically to see how

things have changed. The sketches below

show how different the Lunar X region can look once the terminator has passed

over it.

Lunar X pastel sketches by Mary McIntyre, showing how the X stands out much better when it's on the shadow side

The Eyes of Clavius

Clavius

is the second largest crater on the lunar nearside so it’s a brilliant crater

to observe, even with modest equipment.

It is a roughly circular crater that has a diameter of 225km, but its

location near the southern limb means it appears foreshortened top to bottom so

it therefore looks oval shaped when viewed from Earth. Interestingly, there are

very few truly oval shaped craters on the Moon; almost all oval craters only

look that shape to us because they’re foreshortened by their position near to

the limb.

Comparison of Clavius in a photo by Mary McIntyre with an image from the Lunar Reconnaissance orbiter, showing the foreshortening effect of Clavius being near the southern limb

Clavius has several satellite craters along its floor.

Clavius C and D, with diameters 21km and 28km respectively, have walls that are

higher than the crater floor. As the Sun rises over Clavius, the tops of these

crater walls catch the sunlight before the rest of the crater floor and this

creates two white rings that resemble a pair of eyes looking out from the

shadowy crater floor.

The Eyes of Clavius are visible during a Waxing Gibbous Moon, but as with other

Clair-Obscur effects, the exact phase angle varies each month due to libration.

During 2024 there are notionally seven dates when the Eyes are visible from the

UK but many of them are on a rising, setting or daytime Moon which will make

them much harder to observe. Our best chances are in January and March.

Left side: The Eyes of Clavius shine out from the shadowy crater floor

as the Sun rises over Clavius.

Right side: Clavius fully illuminated with more satellite craters visible

The Jewelled Handle /

Sinus Iridum

Sinus Iridum photo by Mary McIntyreAs

the Sun rises over Sinus Iridum, sunlight catches the tops of the Jura mountain

range, causing a bright semi-circle pattern that shows up through the shadows.

This clair-obscur effect is best viewed at the start time, but the bright arc

along the Jura Mountains remains visible for quite a while, even after the

lunar terminator has passed over the region. When observing this, don’t forget

to look for the shadow being cast by Mount Laplace on the top corner – seen on

the right of the above photo.

Cassini’s Moon Maiden / Promontorium Heraclides

Left: Moon Maiden drawn by Giovanni Cassini in

1679

Right: Moon Maiden photograph by Mary McIntyreHumans are predisposed to see faces everywhere, even in the

most unexpected places; this is a phenomenon called Pareiodolia. In his 1679

map of the Moon, created from telescopic views hence south being up, Giovanni

Cassini depicted Promontorium Heraclides on the edge of Sinus Iridum as a

woman's head with long, wavy hair. It is believed to have represented the head

of Geneviève de Laistre, who Cassini's married in 1673. This makes her the

first woman on the Moon! This Clair-Obscur effect starts to become visible as

soon as the Sun has risen over the area when the height differences and contrast

with the darker maria surface around her create areas of light shade that give

the impression of her face and hair effect. She actually remains visible for through

to Full Moon but the when the whole area becomes so illuminated some of the

surface relief and definition are lost, so she best viewed when the Moon is a

Waxing Gibbous.

I hope you enjoy observing a few more clair-obscur effects

this year. Please feel free to share this blog with anybody who may find it

helpful.

Don’t forget there many other clair-obscur effects that are

well worth seeking out. There is comprehensive list of them on Wikipedia here:

I really hope you found this post helpful. Please feel free

to share the link to this blog or to the PDF version on Dropbox with it with anybody who may find it useful.

Clear skies!

Mary McIntyre FRAS

Astronomy Communicator

PS: Apologies for any funky formatting on this blog. The wysiwyg editor on this software is nothing of the sort and despite several hours of trying to centre the text and images, there are still some titles and paragraphs that are insisting they do their own thing. I'll be investigating other options because this software SUCKS!

My socials:

Website: www.marymcintyreastronomy.co.uk

www.facebook.com/marymcintyreastronomy

Twitter: @spicey_spiney

Instagram: spiceyspiney

Flickr: spicey_spiney

youtube.com/user/spiceyspiney

Mastodon: MaryMcIntyreAstro@astrodon.social