Noctilucent Clouds and How To See Them

By Mary McIntyre FRAS

www.marymcintyreastronomy.co.uk

June and July are difficult months for astronomers in the UK

because have so few hours of darkness. Does this mean less sleep deprivation?

Not a chance, because it’s Noctilucent Cloud season! Noctilucent clouds (NLCs) are one of the highlights of the summer calendar. The 2018 NLC season was one of the best I’ve

ever experienced, and the 2020 season was also very memorable because not only

did I see a display where NLCs were visible up to the zenith, but also I had a

display alongside Comet NEOWISE; I won’t forget either of those in a hurry!

What are NLCs?

Noctilucent clouds (NLCs) are also known as “night shining

clouds” and if you’ve ever observed them you will know they certainly live up

to their name. Visible during deep

twilight, they have a beautiful blueish-white ethereal glow. They are very different from the tropospheric

clouds that we see during the day.

Primarily, it’s due to their altitude. Cumulus clouds are some of the lowest clouds

we see and they reside around 2km above sea level. Cirrus clouds, the thin clouds associated with

ice halos, sundogs and other atmospheric optical effects, are the highest

tropospheric clouds we see (excluding towering thunder clouds) and they reside

at an attitude of around 6 km.

Where are They?

To find NLCs, we need to go much higher. The boundary of the

troposphere is 10km above sea level. Above that we have the stratosphere; a

layer that extends to an altitude of 50km, and it’s unique to Earth. This is where

UV radiation from the Sun breaks down oxygen into ozone to form the ozone

layer. It’s also the home of a kind of polar stratospheric clouds called nacreous

clouds, but they are rarely seen from the UK.

Above the stratosphere, we have the mesosphere and that extends to 85km;

above that is the thermosphere. The boundary between the mesosphere and the

thermosphere is where you’ll find NLCs. Aurora occurs just 15km above this, so

NLCs really are on the boundary of space! NLCs are also seen in the tenuous

atmosphere on Mars, where they reach a whopping altitude of 100km. This makes

them the highest clouds recorded on any planet in the solar system.

Formation and Visibility

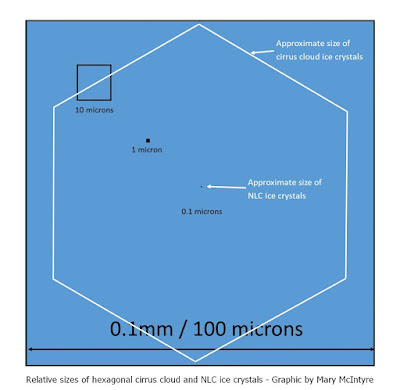

NLCs are polar mesospheric clouds, so they cluster around the Polar Regions. They are made of water ice, but here lies another

huge difference between NLCs and tropospheric clouds; that is the size of the

ice crystals. Cirrus cloud ice crystals that cause halos have a diameter of around

100 microns (0.1mm), so they’re pretty small. However, NLC ice crystals have a

diameter of just 0.1 microns (0.0001mm) so they’re absolutely minute! This is

why NLCs are not visible during the day. The lower levels of the atmosphere

need to be in shadow and NLCs still illuminated from below by the Sun in order

for them to be seen.

For NLC ice crystals to form, a source of water is needed.

The mesosphere is very dry so NLCs may not form every day. The mesosphere must also be below -123

degrees Celsius for ice crystal formation. The temperature of the mesosphere is

colder when the troposphere is warmer, so NLCs can only form during the summer

months. For us in the northern hemisphere, that tends to be from mid-May

through to mid-August with the peak activity in June and July. In the southern hemisphere, NLC season is

mid-November to mid-February.

The ice crystals also need a nuclei to trigger crystal

formation. NLCs had never been reported prior to 1885. Historically, excellent

meteorological observations had been reported so it’s unlikely they would have

been missed. Two years prior to the first reported display there had been a

major eruption on Mount Krakatoa so it was thought volcanic ash particles were

the catalyst. It’s now thought micrometeorite dust is responsible.

Link to Global Warming and Solar

Activity

At one time NLC displays were rare, but they are now observed much more

frequently. One theory is that climate change may be responsible. Human

activity has pushed up the emissions of greenhouse gasses and that has lead to

an increase in temperature within the troposphere. As stated above, an increase

in temperature at that level causes a decrease in temperature up in the

mesosphere. It has also been observed that NLC displays are brighter and more

numerous when the Sun is at the minimum phase of the 11 year solar cycle. When

the Sun is more active there is more UV radiation hitting the atmosphere. As

well as breaking down oxygen into ozone, UV will also break down water

molecules in the higher levels. Because the mesosphere is already quite dry and

tenuous to begin with, UV radiation will remove all of the water and therefore

no ice crystals can form. Solar scientists believe we are currently in a grand

minimum so this may be another reason why we are seeing them more frequently.

How to see them

NLCs may

be visible when the Sun is between 6 and 16 degrees below the horizon, because

this is when the lower levels of the atmosphere are in shadow. NLCs are so high

that they remain illuminated by the Sun so they appear to glow against the

twilight sky. Northern Hemisphere NLCs

are visible from between around 45 and 60 degrees latitude. Any further north

the Sun doesn’t get low enough below the horizon for the lower atmospheric

levels to be in shadow. Because they’re

polar mesospheric clouds, they cluster around the poles. During the northern

hemisphere NLC season, they cluster around the north polar regions. This means

they are usually very low to the northern horizon from mid-latitudes, so only

the largest accumulations of clouds will be visible from further south.

NLCs

become visible around 60 – 90 minutes after sunset and between 60 – 90 minutes

before sunrise, but near to the solstice they may remain visible all night long.

After sunset they tend to be visible towards the north west and before sunrise

more towards the north east. The amount

of NLC visible in each display van vary enormously! Sometimes there is just a

hint of white glow low in the north, other times they can stretch out over a

hundred degrees across the northern horizon and reach all the way up to the

zenith. The two panoramic images below show how different they can appear along the horizon.

They are usually silvery blue in

colour (although they have been reported to appear as red and green) and can

take on a huge variety of structures and patterns. Sometimes they are little

more than a white glow, other times they have intricate structures that look

like reflected ripples of water. They behave very differently from

tropospheric clouds and they are absolutely stunning through binoculars. They

are one of my favourite things to observe and they make a stunning timelapse

subject.

Forecasting

There

is still so much we don’t know about NLCs so they are very difficult to

forecast. As they accumulate and rotate around the pole, they form a characteristic shape called the ~NLC Daisy” because it can resemble petals on a

flower. There is a satellite that

observes and photographs this accumulation each day and if you visit the Space

Weather website - spaceweather.com – you can find the most recent images on

their front page. This gets updated daily and if you see any accumulation

pointing towards the UK, then you’re in with a chance of seeing them. Remember,

the accumulation may not look like it’s anywhere near us, but these clouds are

so high that they will be visible from the UK. The photo below shows the daisy

on 22nd June 2020, the morning that I saw NLCs reaching all the way

to the zenith from Oxfordshire. (Source: spaceweather.com)

There

are several webcams across Europe and the UK that are pointing north (links are

below). If NLC is visible from a location that is an hour ahead of us, then

there is a chance that we may see them from the UK a bit later. I find myself glued to these cameras during

NLC season!

There

is also a great community of NLC spotters on Twitter. If you follow @NLCalerts

and @NLCnet and keep an eye on the #NLCnow hashtag, you will see observers

reporting when displays are happening. If you see NLC yourself, don’t forget to

report it to these outlets with your location to help spread the word of an

active display. Also, don't forget to report your observations to the BAA Aurora/NLC section!

NLCs

may be visible at very antisocial hours, but I think they are truly one of the

most beautiful sights to behold and definitely worth staying up late or getting

up early for!

To

see more of my NLC photos, check out my NLC Flickr album: https://flic.kr/s/aHsmNjiAGt

To

see my NLC timelapse video playlist on You Tube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLE_LPip90NvY7PGahGXpQ5SxwJOiu_DmA

NLC

webcam networks:

http://ukazy.astro.cz/nlc-

https://www.iap-kborn.de/

NB: I originally wrote this

in-depth article for my blog page 7 years ago. Since then I’ve updated it every

year and added new images. This year I’ve re-written the information completely

and broken it down into subheadings so hopefully that makes it easier to read.

Other Sources:

The Cloud Book – How to Understand the Skies by Richard

Hamblyn